Searching for Land for a New Plant

In 1922, after returning home from Europe, Noguchi quickly planned to build a plant for Casale’s ammonia synthesis adjacent to the Kagami plant in Kumamoto Prefecture.

Most of the fertilizer produced in Japan at the time was expensive ammonium sulfate, and so a large amount of cheap, foreign-produced ammonium sulfate began to be imported. A method to produce high-quality ammonium sulfate cheaper than the foreign-produced products was needed. To make this possible, it was necessary to build a new Casale-process ammonia plant.

This process created ammonia by synthesizing water and air and reacting it with sulfuric acid, producing ammonium sulfate. Ammonium sulfate was already being produced at the Kagami plant, but the new plant met with opposition from local fishermen and farmers due to the risks of high-pressure in the synthesis process.

A commencement ceremony for the new plant was held at the Kagami plant on March 10, but the local drainage permit was denied and construction of the plant had to be cancelled. A large sum of money was paid for patent rights from abroad, but there was no building site for the plant. The search began for another suitable location.

The Advantageous Natural Conditions of Nobeoka

Abundant water and air, the basic resources, as well as a large amount of electricity are needed to produce ammonia. Rural Nobeoka had long been known as “riverside Nobeoka” and is known as such even today.

A large amount of electricity could be produced if a power source was developed along the Gokase River system that flows to Nobeoka from Takachiho, Hinokage, and Kitakata. There was no way that Noguchi, Japan’s leading pioneer who had built many dams and hydroelectric power plants, could fail to see this. Nobeoka was the best location to obtain water, air, and electricity to make fertilizer.

Fish weirs are used in the rivers of Nobeoka

Fish weirs are used in the rivers of Nobeoka

The Gokase River Power Company is Founded

In the spring of 1919, three years before the plan to build the new plant next to the Kagami plant, Yoichi Nagamine, a member of the House of Representatives elected from Miyazaki Prefecture, worked to attract a plant to Miyazaki Prefecture with power development. He visited Tokugoro Nakahashi (the first chairman of Nippon Cisso Hiryo K.K.), who was a member of Seiyukai (a political party at that time), and explained the advantages of a power plant along the Gokase River, wishing to attract a plant to Miyazaki Prefecture.

Nakahashi recommended Noguchi as an excellent entrepreneur at Nippon Cisso Hiryo K.K.. Nagamine soon met and talked with Noguchi, and Noguchi went to investigate the site right away.

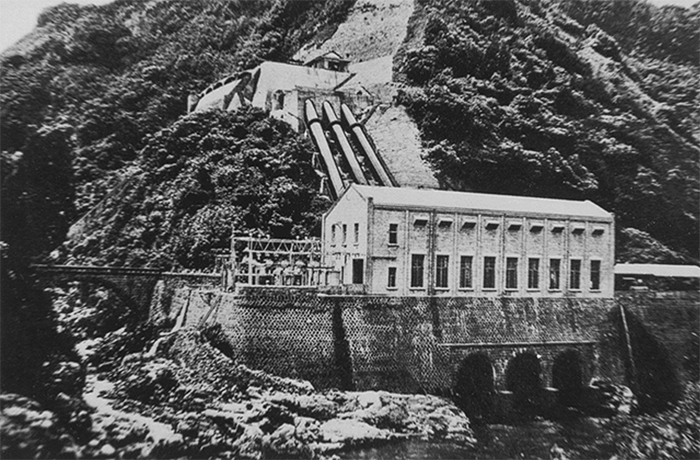

As a result of this investigation, Noguchi decided that it would be extremely advantageous to build a power plant there. In May 1920, he established the Gokase River Power Company in Shinmachi, Nobeoka, and decided to build a power plant in Hinokage. Yaemon Yamamoto, a member of the Tsunetomi village assembly in Hirabaru, supported Nagamine in this effort.

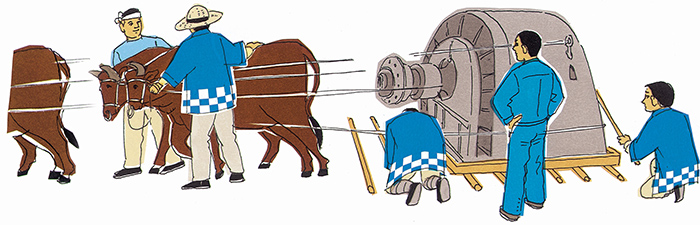

Building a power plant under the blazing sun in July 1920 was no easy task. They used riverboats, transported generators and other heavy equipment with a primitive method using rollers and oxen, and transported cement by horse-drawn wagon.

There were no railroads in Nobeoka at the time. Horse-drawn carriages were the main form of transportation. Boats and horse-drawn carriages were used to travel between Miyazaki and Nobeoka. The power plant was completed in August 1925 and was later purchased by the Nippon Cisso Hiryo K.K., supplying the fertilizer plant in Nobeoka with 12,000 kW of electricity.

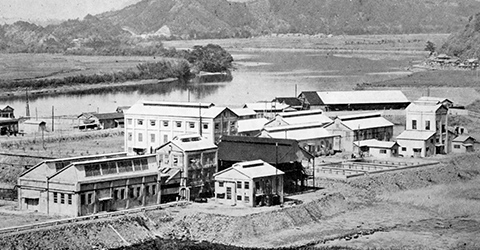

Gokase River power plant (currently Hinokage Town)

Gokase River power plant (currently Hinokage Town)

Attracting the Plant and the Efforts of Local Supporters

Although Noguchi had previously attempted to build a new plant for Casale’s ammonia synthesis next to the Kagami plant in Kumamoto Prefecture, it didn’t go well and the plan had to be abandoned.

Noguchi visited Nobeoka in March 1922 to search for a location for the new plant. This was when construction of the Gokase River power plant was progressing. At the time, Nobeoka had plenty of land for plants, being a rural area with fields spreading out as far as the eye could see.

The first person Noguchi met in Nobeoka was Yaemon Yamamoto, an executive at the Gokase River Power Company who was a member of the Tsunetomi village assembly. After meeting with him, Noguchi went to the Tsunetomi village office. From there, he was taken to the top of Mount Atago where the whole village could be viewed. Noguchi used his walking stick to point to the area where Asahi Kasei’s chemical plant in Tsunetomi is currently located, saying “I want this much land” while drawing circles in the air. The person with him was astounded at the grandness of the scale.

On March 26, Noguchi returned to theNippon Cisso Hiryo K.K.’s Osaka headquarters, and it was officially decided to build Nippon Cisso Hiryo K.K.the new fertilizer plant in Nobeoka. Active cooperation from local supporters was seen as Noguchi was trying to build the new fertilizer plant in Nobeoka.

Some of these local supporters included Tsunetomi Mayor Ikuji Hiyoshi, and village assembly members Yaemon Yamamoto, Tadami Miyake, Teruo Shiga, Toyoji Monma, and Washitaro Kasahara. These supporters actively worked to secure land for the plant, explaining to the village assembly the importance of attracting a plant to the village. They believed that attracting a plant to Nobeoka would lead to the future development of the area.

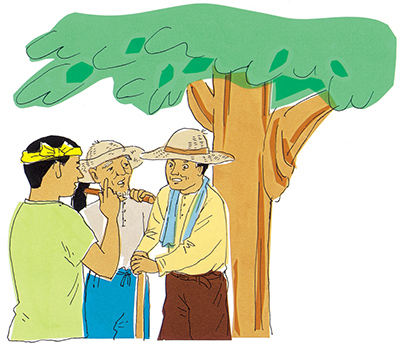

But after it was decided to attract the fertilizer plant to Nobeoka and sale of the plant land had begun, strange rumors began to spread. One rumor said that the air around Nobeoka would become thin as the new fertilizer plant would take nitrogen from the air. Another said that if the plant exploded, debris would fly off in every direction. Because of such rumors, some people began to oppose selling the land.

When this was brought before the village assembly, Assembly Member Kasahara, a graduate of Tokyo Imperial University who was the former chief engineer of the Hibira copper mine operated by the Naito family, gave a simple scientific explanation, suggesting that if they had a look at the Kagami plant in Kumamoto, they would understand. He organized a tour of the plant and this reassured the group of observers. The observers then went to each area to negate the false rumors, and the land for the plant was sold in only four months.

You can get a sense of the foresight of the Mayor and the local supporters who were involved in inviting the plant that set the path for Nobeoka’s future development, and their passion towards their hometown.

Most of the local supporters were also graduates of Ryotensha (a private school run by the Naito family). Looking at these circumstances leading up to the new fertilizer plant’s construction in Nobeoka, we can see that the new plant was not established here by chance. This is how the world’s first Casale ammonia synthesis plant was constructed in Nobeoka in August 1922.

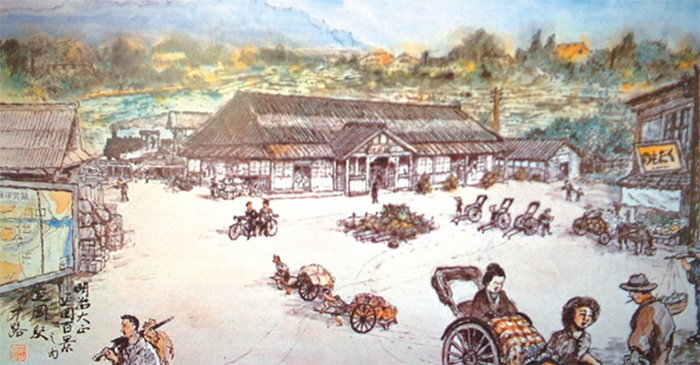

Nobeoka Station around the time it opened in the early 1920s

Nobeoka Station around the time it opened in the early 1920s

(from One Hundred Views of Nobeoka: Now and Then)

Nobeoka Station in 1930s

Nobeoka Station in 1930s

There was also a desire for early construction of a railway, and the Japan Railway’s Nippo Line was fully opened to traffic in December 1923, serving as a major boost towards development of the plant.

This is the story of how a fertilizer plant, the predecessor to Asahi Kasei, was established in Nobeoka. First, there was a desire to create quality fertilizer that was cheaper than foreign-made products. The Casale production process which did not emit foul odors was best suited for this, and there was an attempt to build the new plant in Kagami, Kumamoto.

Second, the advantageous natural conditions of Nobeoka were suited to the production of fertilizer. The abundant water and air, the main resources needed, as well as a large amount of electricity from the Gokase River power plant which was under construction.

Finally, the development of the plant was related to securing land for the plant and a local readiness to accept the plant. The passion of local supporters towards their hometown and their foresight made it possible to attract a plant, and this led to the future development of Nobeoka.

Difficulties from Plant Completion until Operation

The plant was completed in September 1923, but numerous issues had to be solved before the machinery could operate and production could begin. There were issues with the compressors, convertors, circulators, and other machinery, as well as for training the technicians.

Noguchi gathered a team of brilliant young technicians from around Japan. If an accident were to occur under the high pressure of 750 atmospheres, it would be fatal. The technicians came to work at the plant after toasting to each other’s safety with cups of water.

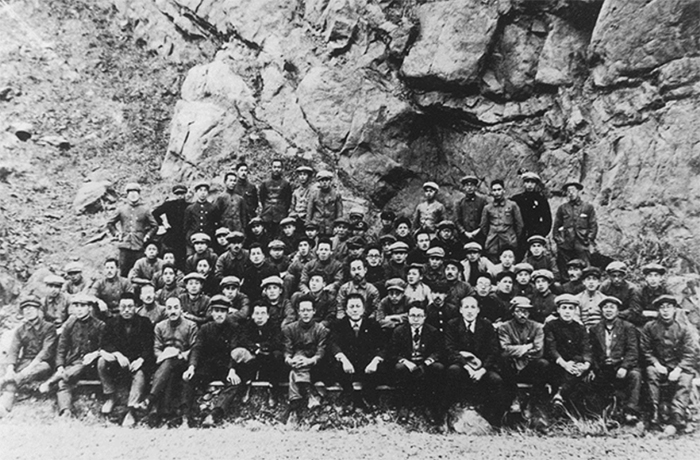

Technicians when the plant was founded, under Mount Atago

Technicians when the plant was founded, under Mount Atago

Commercial operation of the ammonia synthesis process wouldn’t have been possible without the efforts of these technicians. As for the machinery, there were repeated struggles and trial operations, but after various improvements were made the plant was finally perfected.

An ammonia convertor is preserved as a monument at the Casale Plaza

An ammonia convertor is preserved as a monument at the Casale Plaza

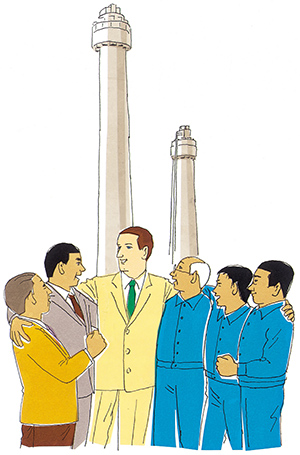

At 4:30 in the afternoon on October 5, 1923, just as the autumn sun began to set, shouts of joy were heard from the plant at the base of Mount Atago in Nobeoka, which had become the subject of attention from scientists around the worldNippon Cisso Hiryo K.K..

“Hurrah! We did it!” With their arms around each other’s shoulders, everyone was nosily cheering with excitement and joy. With the inventor Casale himself present, it was an emotional moment as synthetic ammonia was made for the first time in Japan.

This was a historic accomplishment in the history of the chemical industry in Japan. It was also the dawn of Nobeoka’s transition into a modern industrial town.

Expansion and Development of the Plant

With the success in creating synthetic ammonia, the Nippon Cisso Hiryo K.K. successively built other plants in Nobeoka for Bemberg, viscose rayon, explosives, and more.

Previously, in May 1922, Noguchi established Asahi Fabric Co., Ltd. jointly with Matazo Kita, president of Japan Cotton Trading Co., Ltd. Noguchi had seen a kind of artificial silk called viscose rayon in Italy, and was impressed with its quality. He tried to convince people in Japan of the prospects for this artificial silk, but few were interested.

Talk of a viscose rayon plant in Nobeoka began in May 1924. Activity to attract the plant to Nobeoka began immediately. Okatomi Mayor Kawasumi was especially passionate. With his eye on the clean waters of the Hori River, Noguchi signed an agreement to buy land (the entire Nakagawara area of 396,000 square meters) for the plant in the village of Okatomi.

The chemical plant in the late 1920s

The chemical plant in the late 1920s The chemical plant in the early 2000s

The chemical plant in the early 2000s

The Bemberg plant in the late 1920s

The Bemberg plant in the late 1920s The Bemberg plant in the early 2000s

The Bemberg plant in the early 2000s

Construction work began on the plant but had to be halted due to the company’s lack of funds, and there was no prospect of completion. Residents of the village of Okatomi barged in to the village office because they could not make a living anymore after losing their farms, and they petitioned to have the construction restarted.

Aside from this, Noguchi went to New York in January 1928 and signed an agreement with J.P. Bemberg of Germany for the Bemberg™ cupro fiber patent. The following year in 1929, Japan Bemberg Fiber Co., Ltd. was established with 10 million yen in capital.

News of a Bemberg plant being built in Okatomi broke next, but the location changed to Tsunetomi. The village of Tsunetomi was ecstatic over the building of a Bemberg plant, but one of the conditions mentioned by Noguchi was for the land to be provided free of charge. The village didn’t have that kind of money, so Noguchi offered another proposal. “If the villages of Tsunetomi and Okatomi merge with the town of Nobeoka by April of next year, I will donate the money to buy the land.”

Nobeoka at the time was still divided into two villages and one town: the town of Nobeoka (Kawanaka district), the village of Okatomi (Kawakita district), and the village of Tsunetomi (Kawaminami district). In many ways, a future here in three separate municipalities was inconvenient to Noguchi, who wanted to create a single, large industrial area here.

The viscose rayon plant in the late 1920s

The viscose rayon plant in the late 1920s The viscose rayon plant around 2000, with operations discontinued in September 2001

The viscose rayon plant around 2000, with operations discontinued in September 2001

With Noguchi’s statement, momentum towards merging quickly escalated. The new town of Nobeoka was established in April 1930, becoming Nobeoka City three years later on February 11, 1933.

The Bemberg plant was completed on schedule in April 1931. The viscose rayon plant, whose construction had been halted, was also completed in December 1933, and operations commenced. Many employees at the viscose rayon plant came from other parts of Miyazaki prefecture and around Japan, and the area around the plant was invigorated, with shops opening up one after the next.

Because Noguchi believed in taking care of employees, the Bemberg and viscose rayon plants also had modern, three-story reinforced concrete boarding houses with flushing toilets for the women who worked there.

Many female employees from all over Japan lived there, and were provided continuing education in tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and cooking on their days off and in the evenings, something that was extremely rare at the time.

The explosives plant in the late 1920s

The explosives plant in the late 1920s The explosives plant in the early 2000s

The explosives plant in the early 2000s

In 1948, Asahi Elementary School opened after separating from Okatomi Elementary School, and in 1958, Asahi Junior High School opened after separating from Okatomi Junior High School. At the peak, there were about 1,800 students at Asahi Elementary and over 900 students at Asahi Junior High, of whom 30 to 40% were children of Asahi Kasei employees.

Asahi Elementary and Junior High Schools were named after Asahi Kasei, and this shows just how great an impact Asahi Kasei, the company founded by Noguchi, had on education in Nobeoka and on the city itself.

As the Bemberg plant was being built, the Japan Nitrogenous Explosives Company (precursor of the current explosives plant) was established in December 1930 in the village of Tomi and production of explosives began.

Asahi Kasei expanded its plants with a policy of diversification successively creating by-products using the originally developed synthetic ammonia as a base. Only a decade after the establishment of the ammonia plant, Nobeoka had evolved into a major industrial complex for basic chemicals, fibers, explosives, and more.

In 1933, Japan Bemberg Fiber Co., Asahi Fabric Co., and Nobeoka Ammonia Fiber Co., merged, adopting the name Asahi Bemberg Fiber Co., Ltd., creating an artificial fiber company with 46 million yen in capital. This was the predecessor to today’s Asahi Kasei Corporation.

Nobeoka changed remarkably along with the expansion and development of the plants. The small town was rapidly transformed into an industrial city, and by the 1940s, roughly 40% of the population were involved with the plants.

Local poet Bokusui Wakayama wrote this poem:

How nostalgic,

The bell from castle hill.

As I heard it as a child,

I hear it now, too.

The person who struck the bell that Bokusui heard was Kome Inada, known by residents as the “Bell-ringing Lady” of castle hill. Kome, who died at the age of 71 in 1971, rang the bell on the 53-meter high hill where the castle used to stand every day for 51 years while looking across the city that spread out in front of her. She was a living witness of history, having fully understood the changes of the area with her own eyes. She had this to say:

“Nobeoka has changed. When I began ringing the bell, it was a little town and there were no trains. It was nothing but fields, and pitch black at night. The stars were really beautiful. Then plants and tall smokestacks were built here and there, and the vestiges of the past were gone.... It was enchanting to see the beautiful neon and lights of the plants in summer....”

This is a valuable eyewitness account of the changes to Nobeoka before and after the construction of the new synthetic ammonia plant in Nobeoka, which began operations in October 1923. It shows how Nobeoka, which had sarcastically been referred to as a place where man and monkey live side by side in Natsume Soseki’s Botchan, had rapidly evolved into a modern industrial city.