Noguchi’s name as a world-class entrepreneur would go down in history based on his development of hydropower in the Korean Peninsula and his management of a chemical enterprise there using this electricity.

Noguchi developed hydropower on the Pujon and Changjin rivers, built a chemical enterprise in Hungnam utilizing that electricity, and constructed the Amrok Sup'ung Dam in a region now part of North Korea. He decided to expand into the Korean Peninsula when a survey team took on the steep, undeveloped mountains of this area in June 1925, while the Nobeoka business was still growing.

As his business in Japan advanced, Noguchi felt strongly that cheaper, more abundant electricity was needed. This is because the consumption of ammonium sulfate fertilizer at the time was increasing, and as production could not keep up, large amounts of the fertilizer were being imported. To counter the imported ammonium sulfate, Noguchi wanted to increase the production of cheap ammonium sulfate. But the Nobeoka plant expansion was not enough, so Noguchi thought of constructing another even larger ammonium sulfate plant. Cheap, abundant electricity was needed for this.

He had already looked around Japan for rivers that could be developed. There were plans to develop Yakushima island, but an investigation concluded that conditions could not be met. The next idea was to turn to the Korean Peninsula.

The Development of the Pujon

If the flow of the river can be reversed

The Changbai Mountains run along the east side of the Korean Peninsula, forming a steep barrier along the coast. On the other side of the Changbai Mountains is an area of plateaus, with rivers feeding into the Amrok river which flows into to the ocean west of the peninsula. The flow of these tributaries of the Amrok varies greatly between the seasons, running very low in winter. It was generally considered that these rivers were unsuitable as a resource for hydroelectricity.

But there was still some hope if you look at the map closely enough. “Of course! If we dam tributaries of the Amrok, dig a tunnel, and reverse the flow of water eastward, there will be a thousand-meter difference in elevation which can drive a large power plant.” This was Noguchi’s bold idea to develop the Pujon and Changjin rivers, tributaries of the Amrok. This was a huge challenge, something that no one had even considered before.

When Noguchi had had a plan, he was not satisfied with leaving it as is on his desk. It was usual for him to take the lead and join the on-site surveys himself, no matter how bad the climate or conditions were. For this project as well, after deciding it was possible from studying the map, he confirmed this by actually going to the location for a survey. This convinced him that the project was extremely promising. Once again, this shows Noguchi’s robust energy and scientific attitude of hypothesizing, experimenting, and proving as he planned and worked on one project to the next.

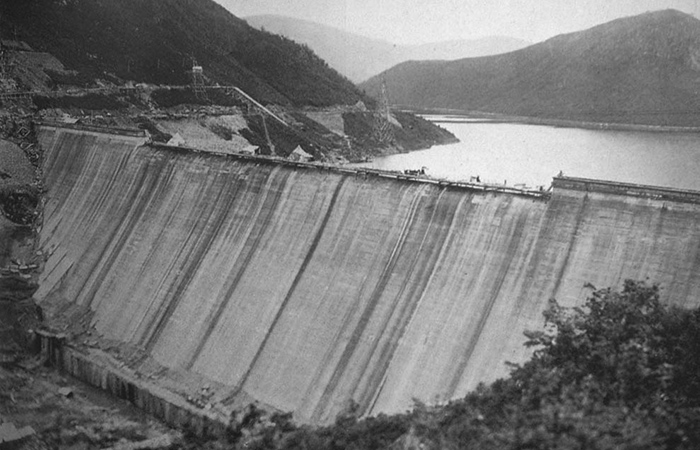

In 1926, he established a company to advance the project with 20 million yen in capital. The Pujon development included stopping water over the entire area and creating a large reservoir with a circumference of 78 km, building a dam, excavating a large, 28-km long tunnel for the water to pass through the mountains, and reversing the flow of the river towards the ocean in the east, laying high-pressure pipes, installing over 800 hydroelectric turbines across the total drop of 1,000 meters, and building an inclined railway. This was the largest construction project in Asia at the time, with a total cost of 55 million yen. The project, based on a radical idea, was completed in 1930 and produced 200,000 kW of electricity.

Pujon dam

Pujon dam

In such a huge project, there are some things that do not go as planned. The civil engineering company that was contracted to excavate the tunnel had underestimated how expensive the work would be, and there were significant cost overruns. Noguchi considered this contractor to be a trusted partner and didn’t want them to incur a loss, so he took responsibility by paying the extra money himself. This shows that the success of such an ambitious world-scale project owes not only to Noguchi’s bold vision but also to his warm heart and the value he placed on the trust of the people he worked with.

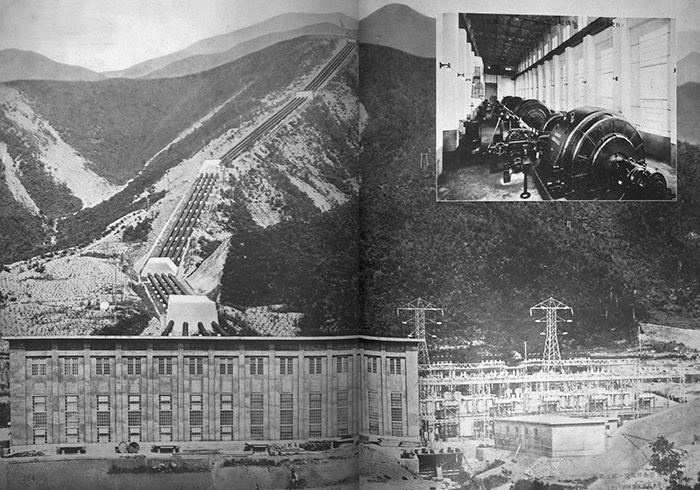

Pujon power plant

Pujon power plant

Construction of the Hungnam Plant

Aiming to construct the world’s second industrial chemical city

The flow of the Pujon was reversed and they had succeeded in obtaining 200,000 kW of electricity, but where was this power going to be used? Deep in the rural mountains of the Korean Peninsula, they built a power plant of several hundred thousand kilowatts. There needed to be land that could be developed for industrial use and start businesses using this electricity not too far away. Noguchi considered Hungnam to be the ideal location for his industrial development.

Prior to development, Hungnam was a fishing village of 20 to 30 homes. In less than a decade, this little village developed into a large, world-class industrial chemical city. In 1927, Noguchi established the Korea Fertilizer Company in Hungnam with 10 million yen in capital and began construction of the Hungnam plant to establish fertilizer and other chemical industries there.

Progress on plants steadily progressed, and, including the world’s largest fertilizer plant, various plants were built for pharmaceuticals, oils and fats, magnesium, zinc, calcium carbide, synthetic gems, carbon, explosives, aviation fuel, synthetic rubber, and more. The city also had a railway, port, and other facilities, growing to over 1,700 hectares including both industrial and residential areas, with 47,000 plant employees and an overall population of 180,000.

In addition to the plants, warehouses, and offices, the city had housing, recreational facilities, sports facilities, hospitals, schools, post offices, a city hall, assembly halls, police stations, and many other facilities. Furthermore, these were all built of brick, had flushing toilets, were fully electrified, and featured steam heating for winter – things that were remarkable at the time.

Hungnam plant

Hungnam plant

Was there any other comparable chemical industrial complex in the world at the time? The Hungnam plant complex was second only to BASF AG’s contemporary group of plants in Oppau, Germany. There were no larger clusters of chemical plants in England, France, or the United States around the same period.

In Japan, it may be possible to consider the group of plants in Omuta or Niihama to be comparable. However, both of these were built up from existing operations over several decades by major conglomerates. Noguchi accomplished the Hungnam development as an individual with no connection to an established conglomerate and without government subsidies. It is truly remarkable that he accomplished this monumental achievement in such a short time.

This project followed Noguchi’s familiar pattern of building hydroelectric plants in tandem with manufacturing plants which use the power. When he wanted to expand production, he looked for a new place to generate electricity. He always looked for undeveloped fields of business and undeveloped areas of land. When obstacles or difficulties occurred, he would tenaciously persist. Ultimately this process led him to expand business overseas.

The Pujon hydropower development and Hungnam industrial development exemplify Noguchi’s fierce spirit and the passion that he dedicated to his projects. They also show his pioneering spirit in taking on the challenge of undeveloped land with resolute determination. There is a sense of purity in this, as well.

Employee housing

Employee housing

Hospital

Hospital

Girls’high school

Girls’high school

A person who was friends with Noguchi said, “The way he acted was refreshing, without any sense of condescension. He seemed to be driven by a pure pioneering spirit.” During his time in Hungnam, Noguchi often said, “If we can supply good, cheap fertilizer, produce will become abundant, Korean farmers will earn a steady living, and this will lead to commercial and industrial development.” Later, Noguchi would transfer his legal domicile from Japan to Hungnam, which he called home for the rest of his life.

An employee who worked at the Hungnam plant recalled an encounter that revealed an unexpected aspect of Noguchi’s personality. “I usually came to Tokyo or Osaka for business two or three times a year. Once, when I was about to go back, the head of administration told me, ‘President Noguchi is going to Hungnam today, but no one is available to attend to him along the way. Since you’re going back at the same time, we want you do it.’ I didn’t have any experience attending to upper management, but I had no choice.

On the express train, Noguchi sat in the first class car and I sat in the adjacent second class car. I was very tired from my business trip, and fell sound asleep not long after the train departed. After some time I woke up and was surprised to find some newspapers and magazines on my lap. Apparently Noguchi had brought them to me after he finishing reading them. Then Noguchi came and gave me an ice cream, and said, ‘You looked tired, did you rest well?’ with a gentle smile before returning to the first class car. I was very moved by this thoughtful and kind gesture. We were usually afraid of Noguchi, since he was known for scolding people.”

Although he had been called autocratic, and was known to scold employees who disappointed his expectations, this account shows another side of Noguchi, who was warmhearted with a common touch and who truly cared for his employees.

The Development of Changjin

A world record in civil engineering

The Changjin is another tributary of the Amrok which starts some tens of kilometers south of the Pujon. It flows gently north in the highlands 1,100 meters above sea level for about 40 kilometers, and then into a ravine. The plan was to build a dam at this point to stop the flow, reverse the flow through a tunnel, have the water spill into the ocean towards the east, and generate about 330,000 kW of power.

Noguchi set his sights on the Changjin for a few reasons. Two years of unusually dry weather meant that the Pujon development was unable to produce enough electricity. Meanwhile, the government’s lifting of the gold embargo caused the price of fertilizer to drop, severely impacting the business. Furthermore, Noguchi was already looking ahead to expanding the electrochemical operations at the Hungnam plant, which would require a large amount of power.

Changjin dam

Changjin dam

Noguchi often said, “When business is bad, we should get moving. When business is good, everyone spends money and things become expensive, but during a recession, contracts are cheap.” The deep recession that occurred after completion of the Pujon and Hungnam projects only served to further spark Noguchi’s entrepreneurial spirit.

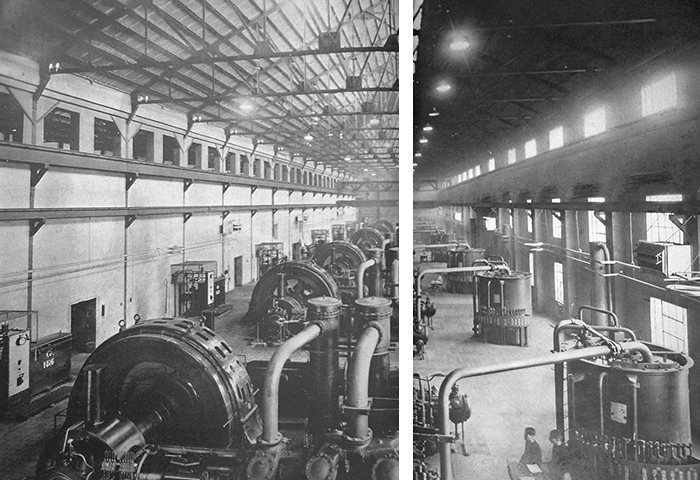

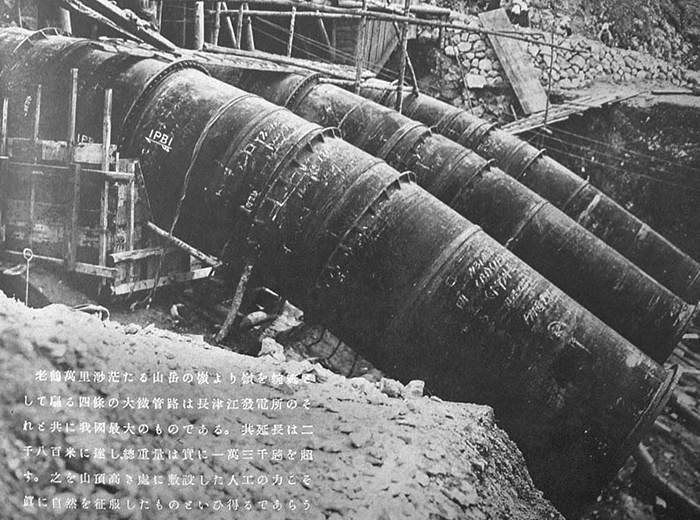

Construction began in June 1933. The Changjin project was a huge civil engineering challenge, even bigger than the Pujon project. Three million bags of cement were needed for the 616-meter wide, 38-meter tall dam. Boring the high-pressure water tunnel 24 km long and 4.5 meters in diameter 40 to 70 meters underground was particularly difficult. Despite these challenges, it was completed in only two years. This was a new world record in civil engineering.

High-pressure pipes

High-pressure pipes

The Development of the Amrok River and the Sup'ung Dam

A world miracle

Noguchi was in his prime as a businessman, having developed the Pujon and Changjin rivers and built Hungnam into an industrial chemical city with a population of 180,000. There was still one more big project that would depend on Noguchi’s great skill: a development of the Amrok river straddling the border between Korea and Manchuria (China).

The Amrok has a watershed of 60,000 square kilometers, and an average annual flow of more than 800 cubic meters per second. To develop this giant river, it was decided to conduct a survey of the actual area despite the considerable complications that were anticipated. A dam could be built anywhere along the course of the river, and as there was an ample volume of water, at least 2 million kW of power could be expected. The plan was to build seven dams along a roughly 500 km stretch from 500 meters above sea level to close to the sea, with a total power capacity of 2 million kW. It was quite an ambitious plan.

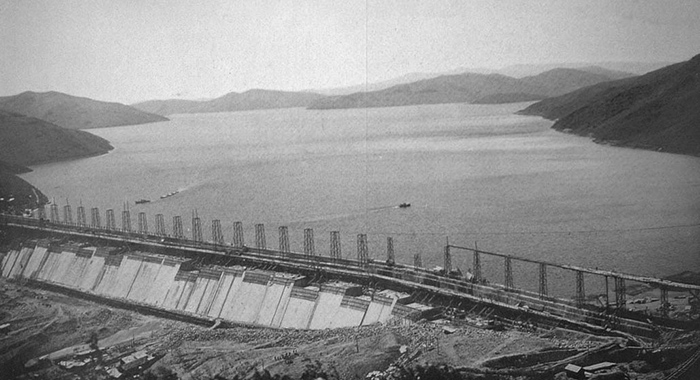

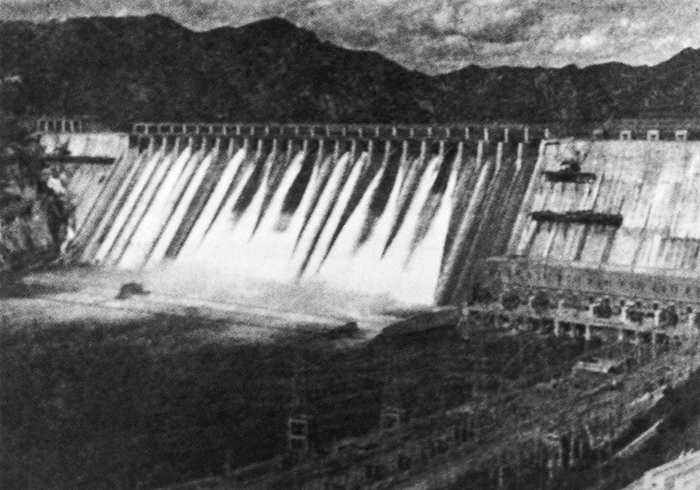

Noguchi was unsure which of the seven dams to build first, but it was decided to start with the Sup’ung Dam. Some 900 meters wide and 170 meters tall, the Sup’ung Dam would create an artificial lake second in size only to that of the Hoover Dam. It was located about 120 km from the mouth of the river, about 80 km upstream from Sinuiju and Dandong. The 100,000 kW generators installed in the power plant were the largest in the world.

A person who visited the dam while it was being constructed said, “I saw it when the second phase of construction had just been completed, and they were going to start generating power soon. The scale of the dam and the equipment was absolutely astounding. Everything seemed like it must have been the largest in the world to me. I truly admired Noguchi for his grand perspective, his big heart, and his ability to get things of such magnitude done.”

Sup’ung Dam was completed, supplying cheap, abundant electricity. In addition, the lower water level below the dam allowed more than 10,000 hectares of rice paddies to be reclaimed. Furthermore, fish were cultivated in the reservoir, and it became possible to raise cattle and pigs in the surrounding highlands. Even the lumber usually left behind due to inconvenient transportation was utilized to build an inclined railway for the construction.

The entire development may be considered comparable to that of the Tennessee Valley Authority which was established in the United States in 1933 as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal policy.

Sup’ung Dam

Sup’ung Dam