I was finally starting to enjoy work and decided to commit to the company for life when the world descended into an uproar. Triggered by the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937, the Second Sino–Japanese War started, and then the Pacific War finally broke out in 1941.

The government established the National Mobilization Act and numerous other wartime laws, exercising control over the economy more and more for each passing day. It was no longer possible to procure even a piece of steel or a bag of cement without the government’s permission.

Under such conditions, in 1941, I was promoted to be chief of the General Affairs section in my seventh year at the company, although I was acting section chief for the first year because I was “still too young.” I formally became section chief in July 1942.

We didn’t have the General Manager system back then, so sometimes a Senior Managing Director doubled as the chief of sales. The chief of General Affairs back then had roughly the same powers as today’s General Managers of General Affairs, Human Resources, Labor, and Administration, as well as the chief secretary. I attended meetings of the board of directors as a facilitator, but Mr. Hori often asked for my opinion, saying “What do think, Miyazaki?”

As the war became more intense, there were more and more negotiations with the military and the authorities, for example to convert factories to produce military supplies. I also came to serve as the chief of General Affairs of the Tokyo office in January 1944. Employees kept getting conscripted, and feedstocks and materials couldn’t be procured as planned, so it was extremely difficult to keep the factories running at capacity.

As this situation wore on, I was finally called up myself in June 1945. I joined the cavalry of the 18th Division in Kurume, Kyushu. Since I didn’t get any military training during university and didn’t have any credits, I was considered a private second class.

Saipan fell, Iwojima was devastated, and we were losing all across the Pacific. There were no good barracks, and we were put in a stable. My unit consisted of 97 men, but we only had three guns.

We had no beddings but slept on straw with our clothes rolled up as the pillow. The meals were meager, consisting of half-cooked rice prepared in a mess kit, miso soup, and pickled daikon radish. It was hard for me to even swallow for some time.

The military can be summarized in just one word: inhuman. Especially us privates were treated as lowlier than horses. For example, if soldiers collapsed on the side of the road during running, they would just be left there without calling a doctor. When non-commissioned officers and long-serving soldiers came back from an outing, it was also the privates’ job to remove their gaiters and take off their coats. To take a bath, privates had to go outside naked and run to the baths wearing nothing but a headband.

I was the oldest and the section chief of a big company, so I was treated relatively well, but seeing these things, I was convinced “There’s no way we can win this war.”

However, two weeks after joining the unit, I was suddenly notified of my discharge by order of the Minister of the Army.

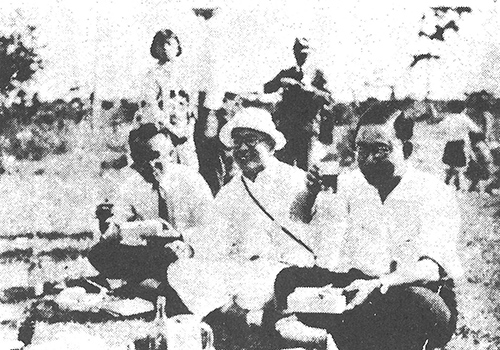

Miyazaki relaxing during a hike when he was the

Miyazaki relaxing during a hike when he was the

chief of General Affairs(furthest to the left)

Back then, Chisso was making propellant for the rockets attached to the wings of fighter aircraft, and the reason for my discharge was that I was needed for that. I was happy about this unexpected good news, but I couldn’t believe it at first since I didn’t think I would go home alive.

On the night before my discharge, my comrades with whom I shared the stable all gave me a piece of tofu from their supper to celebrate my discharge. It was the finest farewell gift I could have gotten.

On the day of my discharge, my squad leader saw me off at the gate and I headed for Kurume Station by bus, and that was the first I actually felt “Wow, I can go home alive.” Of course, I still worried that they might come and cancel the discharge, and when the military police came in to Kurume Station as I was waiting for the train, I thought “Maybe it was a dream.”

That day, I stayed at the house of my older brother in the countryside, but when I woke up the next morning at 5 a.m. and just looked up at the ceiling, I noticed it looked different than usual. “That’s right, I was discharged!” I earnestly enjoyed the happiness of being free. That was the happiest moment of my life.

I heard that my unit left for Okinawa after that.