Let me turn to technological development. The fate of a manufacturing company hinges on having technological development ability. Everyone would like to increase this ability, but that’s not easily done. Obviously you need to gather excellent engineers and researchers, but that alone isn’t enough for creating revolutionary technology and products.

Although such personnel may be very good in their own respective areas of specialization, they aren’t so good at making connections with other fields to create something completely new. But the potential to create original technology comes from linking method A with method B to produce a new method C. Corporate leaders don’t need to know the technical details, but should have ideas and inspiration for how to reach method C.

A good example of this is our development of ion-exchange membranes and ion-exchange resins. The research started around 1950 when Yoshio Tsunoda (later the President of Asahi-Dow) and I were visiting the US. We saw a newspaper article that said, “Fish live in the sea, but why doesn’t their flesh taste salty?” Reading this article, Tsunoda said, “It would be interesting to study how fish skin works.” I was intuitively intrigued as well.

After returning to Japan, we launched a research project. After a lot of trial and error, we figured out how to create membranes permeable to either cations or anions by chemical treatment of membranes made from polymers such as styrene and divinylbenzene.

Our first idea for industrializing this function was to extract salt from seawater. Experiments at the Kawasaki plant went well, but failed when we tried it at Onahama (Iwaki City, Fukushima) where we planned to build a new plant. Some of the researchers started making unscientific excuses, saying the seawater must be different in Kawasaki and Onahama. It was a desperate struggle.

After 10 years, R&D expenses ballooned to more than 1 billion yen, which was an enormous sum back then. This naturally attracted criticism inside the company, but I continued to support the project because I sensed potential for future business.

It took 11 years from the start of research until we established our technology to produce salt using ion-exchange membranes. We built an ion-exchange membrane plant in Kawasaki and our affiliate Shin-Nihon Kagaku Kogyo built a plant to make salt in Onahama, which started operating in 1961.

Since then, conventional salt evaporation ponds and salt-making machines have gradually been disappearing, and nearly half of Japan’s table salt production is done by companies affiliated with Asahi Kasei.

Next we began developing an ion-exchange membrane process to produce caustic soda. At first the research mainly focused on using two membranes for electrolysis of brine, but I was skeptical about the economic viability of this. I asked Maomi Seko, who was the leader of our ion-exchange membrane research, to reconsider this approach. Seko’s answer was just what I was hoping for.

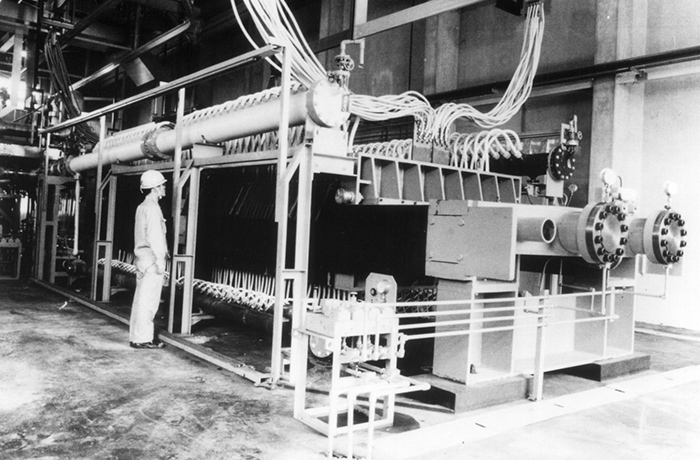

The focus of research switched to using a single membrane with two different chambers in the electrolyzer. We built a big caustic soda plant using this method to perform trials. Seko and his technical team went through a series of struggles, but in the end they successfully developed the world’s first process to produce caustic soda using a single ion-exchange membrane.

We have now licensed this technology to companies around the globe, and the Asahi Kasei process is used for about 60% of all the caustic soda in the world produced using ion-exchange membranes.

In addition, our ion-exchange membrane and ion-exchange resin technology is also used in areas such as seawater desalination, wastewater recycling, production of adiponitrile as an intermediate for nylon 66, and uranium enrichment. This technology has very bright prospects.

In particular, the chemical exchange method for uranium enrichment developed by Asahi Kasei is a revolutionary technology that is not only potentially more inexpensive than conventional methods such as centrifugation and gas diffusion, but also one that can only be used for peaceful purposes. We have already built experimental facilities, so all that is left is the question of economic viability.

I think it’s important for the upper management to have a different perspective from the engineers, and to be committed to seeing a project through to the end.

Caustic soda plant using ion-exchange membranes and membrane sysytems, Nobeoka 1975

Caustic soda plant using ion-exchange membranes and membrane sysytems, Nobeoka 1975